Opportunities seized upon, a mysterious falling out, royal approval and awards, struggles and renaissance – through more than 200 years Waterford and the visionary characters behind its evolution have crafted a unique story in glass.

1700'S

Imagine the times. In 1783, when Beethoven was publishing his first works and the world’s first hot air balloon launched in Paris, in Waterford City George and William Penrose petitioned Parliament for aid to establish the manufacture of flint glass in their Waterford Glass House. They were successful and established an extensive glass manufactory in Waterford City on the 3rd October 1783. By the following year the factory was in full swing and the Penroses made all kinds of useful and ornamental flint glass of “as fine a quality as any in Europe”. They had gathered a large number of the best craftsmen, blowers, cutters and engravers, by which they could supply every article in the most elegant style. It cost the Penroses £10,000 to build and equip the factory, which at first employed 50 to 70 workers. In 1785, mention is made of a Mr. John Hill, “a great glass manufacturer of Stourbridge” who had gone to Waterford, and taken with him the best set of workmen he could get in the county of Worcester. This John Hill was a key figure in the whole enterprise. The Penroses were businessmen who knew nothing about the making of glass. So John Hill was brought in as a compounder, the only man who knew the secret of mixing the glass materials. It was also Hill’s decision to polish the glass after cutting, therefore removing the ”frosted” appearance, which was later to become one of Waterford’s key signatures. John Hill did not stay long in Waterford.

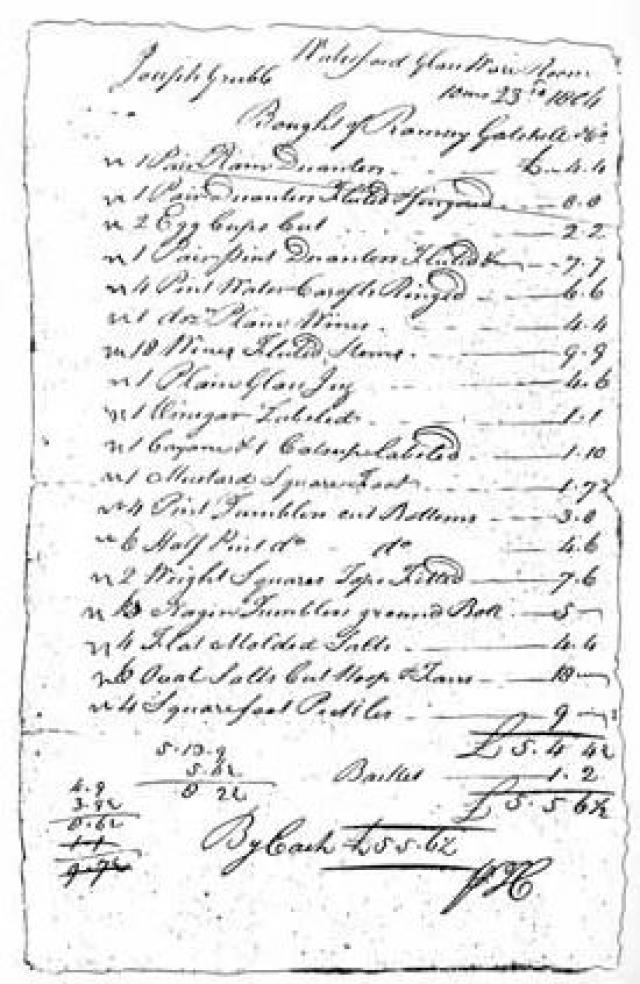

Three years after coming to Ireland he was falsely accused of some act by one of the Penrose family, and took the affair so much to heart that he left Waterford forever. But before he left he passed on his formula for glass compounding to the clerk Jonathan Gatchell in gratitude for his sympathy and understanding in the crisis. So Jonathan left his clerk’s desk and became a compounder. Later he was to rise higher still. Internal troubles notwithstanding, the renown of Waterford cut glass continued to grow and soon it was entering the export market on the grand scale. The Dublin Chronicle of 21st August, 1788, noted that “a very curious service of glass has been sent over from Waterford to Milford for their Majesties’ use, and by their orders forwarded to Cheltenham, where it has been much admired and does much credit to the manufacture of this country.”

William Penrose died in 1796 and the family carried on until 1797, when the business was advertised for sale. Negotiations evidently went at a leisurely pace; for it was not until 1799 that the new company took over. The partners were James Ramsey, Ambrose Barcroft and Jonathan Gatchell, whose skill in compounding now earned him a partnership.

1800'S

Ramsey died about 1810 and the partnership was dissolved. This was Jonathan Gatchell’s moment of destiny. The boy who had joined the Penroses as a clerk in 1783 now became sole proprietor of the glass house and remained in command until his death in 1823, altogether an association of forty years. It seems logical to think of him as having had the greatest influence on the Waterford glass house. Jonathan took over at a time when the glass-making industry was facing new difficulties. The new proprietor had to face a new law, imposed in 1811, which decreed that flint glass made in Ireland and exported was liable to duty: hardly a happy omen for the future since Jonathan had had to mortgage the glass house to raise the money to take over the business. Wages were high, his employees numbered between 70 and 100, and the monthly wage bill often came to £240.

Jonathan had married late in life and on his death in 1823 he left a widow, Sarah, and three young children, George, Frances and Isabella. According to the will, George was to take over the glass house upon attaining his majority in 1835. Until then, the family carried on in various partnerships, during which time the most notable event was the introduction, in 1826, of a steam engine to drive the cutting wheels. On taking over, young George evidently felt the need for some older head in the business, for he took a certain George Saunders, who had worked with the firm for many years, into a partnership that lasted until 1848. Gatchell then carried on alone until 1851. But George Gatchell had really taken over a struggling business.

The industry suffered another crippling blow in 1825 when an additional duty was placed on all glass made in Great Britain and Ireland. The Waterford factory struggled on for another quarter of a century but the writing was already on the wall.

George did his best. He maintained the Waterford standards, winning silver medals at the Royal Dublin Society’s Exhibitions of 1835 and 1836 for cut flint glass, including a richly cut glass flower vase and dish. At the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, he showed an ornamental center stand for a banqueting table, consisting of forty pieces of cut glass, so fitted to each other as to require no connecting sockets of any other material. Nevertheless, by October it was all over. When the Waterford factory ceased production, many of the workers went to Belfast, where the glass-making industry struggled on until 1870. The Pughs in Dublin held on until 1896 when the making of flint glass in Ireland ceased. George Gatchell left Waterford in December 1851 and spent the rest of his life in England, where he died sometime between 1880 and 1890. So ended the first phase of the story of Waterford.

1900'S

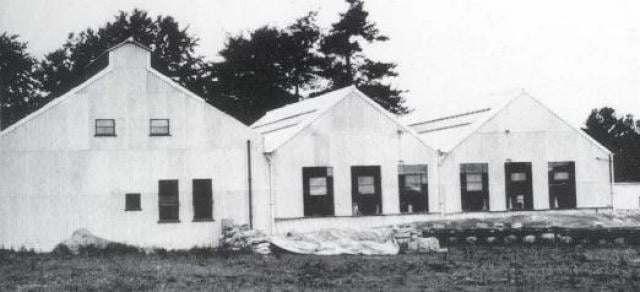

We pick up the story again after the Second World War when, faced with the Communist take-over of his native Czechoslovakia, Charles Bacik came, via various other countries, to Ireland to help set up a crystal factory. In 1947, while Europe was still in ruins after the Second World War, a small factory was set up in Ballytruckle, a suburb of Waterford, one and one-half miles from the site of the original Penrose glasshouse.

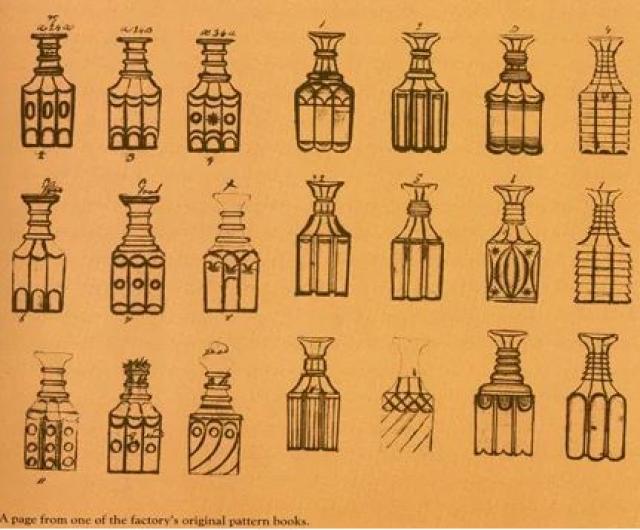

Charles Bacik and Noel Griffin travelled to the Continent. They recruited approximately 30 blowers and cutters from various parts of Europe, who came to Waterford to train young Irish apprentices; among the new arrivals was Miroslav Havel, a blower from Czechoslovakia. Bacik persuaded Havel to come and work in his Waterford factory, promising a fine country that had plenty of oranges and bananas! So on 29th July 1947, Havel left Prague and made his way to Ireland. on board the afternoon international train through Germany and Belgium, and he then boarded a ferry across the English Channel to Dover in England. From Dover, Havel resumed the train journey to London’s Paddington station and then onto Fishguard, where he got the ferry to Ireland. Once here, Havel made as his first task a studious inspection of the old pattern books from the defunct Waterford Flint Glass Works of the previous century, which were stored in the National Museum in Dublin.

This study would greatly influence the first patterns, or suites, to be produced at the Johnstown factory. Through the years, Havel has been the chief designer. He could blow, cut, sculpt, paint and engrave, and he designed the Lismore pattern, which became the most popular pattern ever made by Waterford.

The new factory progressed and, in 1950, Bacik, Fitzpatrick, McGrath, Griffin and a number of other prominent businessmen injected further necessary capital. Joseph McGrath became Chairman and Joseph Griffin became Managing Director of the reorganised company. A move to a larger site in Johnstown, nearer to the city centre was necessary due to increased growth. Newer and better furnaces were built in 1951 and Waterford began its amazing second phase, which, ultimately, was to take the company to the summit of the world's crystal industry. It was in 1955 that Waterford made its first profits. At the time, word of mouth was its best form of advertising by visitors to Ireland, and in 1958 it was decided to no longer do business through the New York agent and to go it alone. Waterford sold from its factory direct to the stores.

During the 1960's and 1970's demand for Waterford expanded dramatically, and that demand soon began to exceed supply. Consequently, the glass works grew in size and stature to become the best-known name in hand-crafted crystal. The brand was by now firmly established. Johnstown was no longer large enough to cope and so in 1970 a new factory was opened in Kilbarry. It was to be built in many stages because ever more space continued to be needed. Before the final stage of Kilbarry was completed, Waterford bought land at Dungarvan and built a factory there with the same process as Kilbarry. It was in July of 1973 that Waterford completed the Kilbarry plant at 425,000 feet, almost 10 acres – the largest manufacturing unit of its type in the world. After the oil crisis of the winter of 1973 – ’74, Waterford planned another factory, this time for lighting ware, for which the demand was so great that it was impinging on normal production.

The demand for Waterford remained huge and Waterford Glass Ltd. became a public company in 1966. In the 1980's computer technology improved the accuracy of the raw materials mix, known in the crystal industry as the “batch”. Pure raw materials are consistently blended for much greater accuracy than was possible a century or two ago. The latest furnace design, one that uses natural gas instead of oil, was introduced in November 1986 and saved the company £2 million on its annual oil import bill. In addition, the research and development portion of the company identified the major cost and quality improvements that could be realized through the use of diamond wheel cutting. Introduced into production in 1987, diamond wheels have assisted Waterford craftsmen in creating even more exciting and intricate patterns.

In 1986 Waterford Glass Ltd. acquired Wedgwood, the prestigious North Staffordshire pottery in England that has specialised since 1759 in exquisite bone china and earthenware. Wedgwood is arguably the greatest name in ceramics in the world today and was strong in markets where Waterford needed to develop. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, Waterford was hit by a severe financial crisis. This was due mainly to a dramatic fall in the value of the dollar, a decline in demand, inflationary labour agreements, and unsuccessful and costly restructuring attempts. But in 1990 new investors turned the trend around with a cash injection.

Waterford launched the Marquis brand in 1991. This extensive range of crystal products, including stemware and hollowware pieces, was the first brand in the company’s two-hundred-year history fine enough to carry the name, Waterford. New products were introduced from the finest crystal facilities in Europe in 1992, all manufactured to the same exacting standards as Waterford. Work practices in Waterford were then revolutionised. An investment in technology over five years was a major contributor in the rapid turnaround to success. In February of 1993, Waterford received a grant from the Industry Research and Development Initiative for new glass melting technology.

The Waterford Wedgwood Group has also enlisted the help of celebrities to promote its brands. John Rocha’s Waterford designs were an overnight success, as were British designer Jasper Conran’s designs. Other acquisitions made by Waterford Wedgwood include the ceramic companies Rosenthal and All Clad.

2000'S

Perhaps Waterford's greatest promotion to date has been the Times Square New Year’s Eve Millennium Ball – an estimated 1.2 billion people watched with awe and amazement as the six-foot diametric crystal ball was lowered down the pole during the New York year 2000 countdown. During the difficult financial crisis in 2008, the Waterford Wedgwood Group and associated companies were unable to secure additional financial revenue to maintain the operation of their global business. On 30th January 2009, it was announced that Waterford was in receivership.

Since then, following the difficult financial crisis of 2008, Waterford briefly went into receivership at the beginning of 2009. KPS Capital, a US based equity firm subsequently purchased some overseas assets and businesses of the Waterford Wedgwood Group, and in January 2010 WWRD Group Holdings Limited (owners of the Waterford, Wedgwood and Royal Doulton brands) announced that it had signed an agreement with Waterford City Council to open a new Waterford manufacturing facility and retail outlet in the very heart of Waterford. The new Waterford manufacturing facility melts down more than 750 tonnes of crystal and produces more than 45,000 pieces each year using traditional methods. Since its opening in June 2010, over one million people have visited the Retail Store and enjoyed guided factory tours of the manufacturing processes. The latest chapter of the Waterford story opened in July 2015 when Fiskars Corporation (Fiskars), a leading global supplier of consumer products for the home, garden and outdoors, acquired the WWRD group of companies including Waterford, Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Royal Albert and Rogaška. With such iconic brands in its care, Fiskars continues to lead the way in the luxury and premium home and lifestyle products market, specialising in tabletop, giftware and interior décor.

From small beginnings, and thanks to the vision of numerous talented and hardworking individuals along the way, Waterford dazzles around the world into the 21st century.